BLOG Psychological Safety

Psychological safety. An early stage concept?

Some time ago I read the book “The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth” by Amy Edmondson (1). The book is absolutely recommendable. In it, Edmondson describes how, especially in knowledge-intensive work environments where teams are faced with uncertain, complex tasks, work can only be done in a productive manner if the members of the team experience what she calls psychological safety. She sees psychological safety as a prerequisite or even as a driver for learning, innovation and long-term development of teams and their members. In this context, she focuses in particular on the leaders. It is primarily their task to create a climate in which team members dare to ask questions, find it not difficult to ask for help, may contribute ideas or point out problems or even grievances. Since then, many have been talking about the concept of psychological safety as a miracle recipe for innovation, learning and development.

In a first response, I was very taken with these clear and descriptive explanations and yet a lukewarm feeling crept over me. Somehow the idea of psychological safety reminded me of what the great developmental psychologists Mary Ainsworth (2) and John Bowlby (3) already called a “safe base” in the middle of the last century. They make clear that children at an early stage of development need a safe base within which they can explore. And they reasonably describe exploration as an essential basis for experience, learning and development. In the early childhood phase, it is primarily the parents who provide the child with this safe base. Adolescents, on the other hand, have the task of breaking free from this safe base at some point in their lives. They have to learn to assert themselves in an environment characterised by insecurity and to gain security from their own social context, beyond the parental home.

Doesn’t psychological safety describe exactly what Ainsworth and Bowlby described as a safe base? It is possible that psychological safety is a claim that is at best on a rather early or even infantile level? It would fit into a world where caring and coddling are gaining space in the context of what I call “maternalistic leadership”. Don’t we talk more and more about compassionate leadership? And, referring to the much-quoted Abraham Maslow once again: isn’t the need for security the level which also tends to be at the beginning in the ontogenetic development, but the adult human being strives for the higher level of self-actualization?

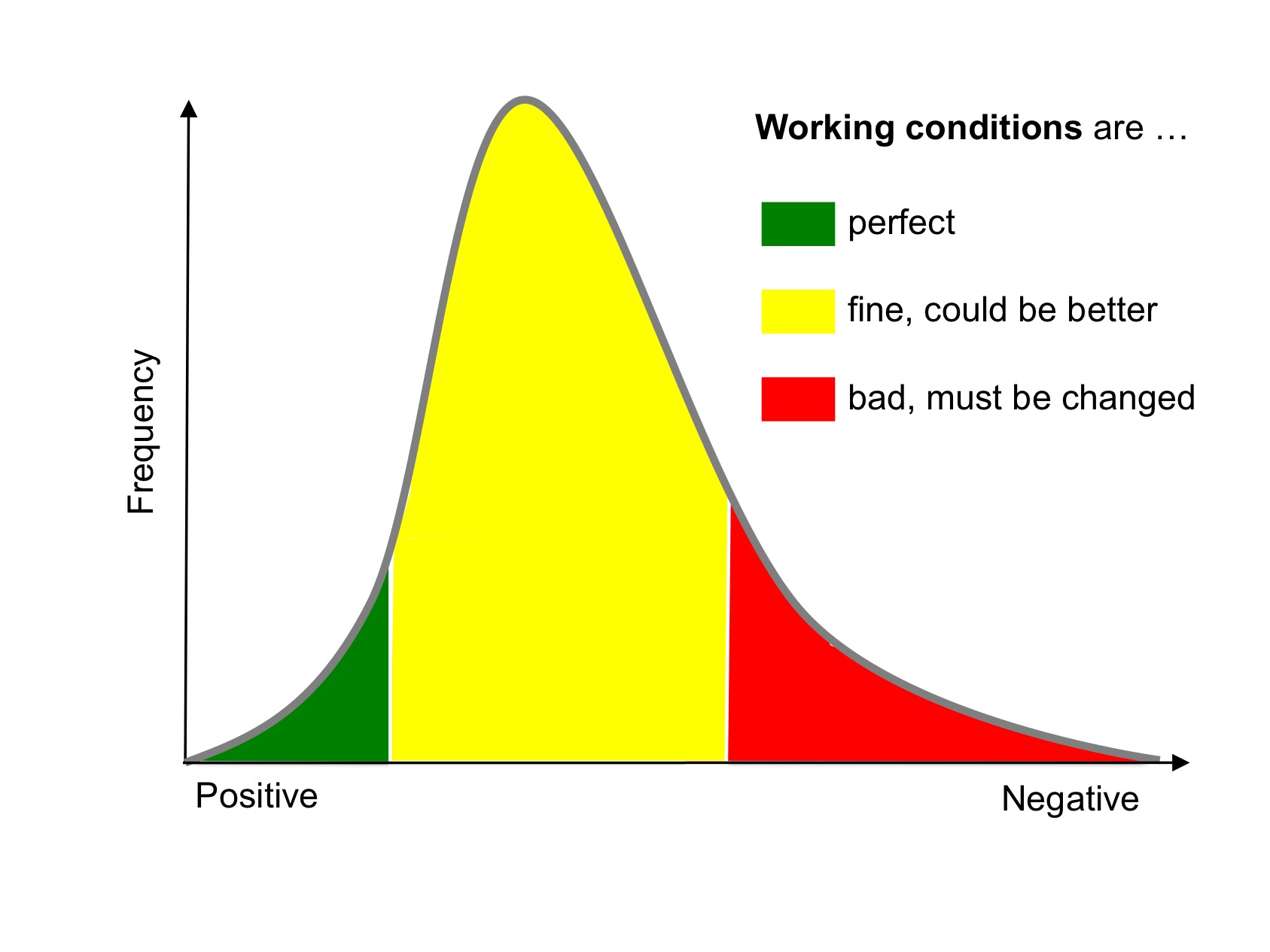

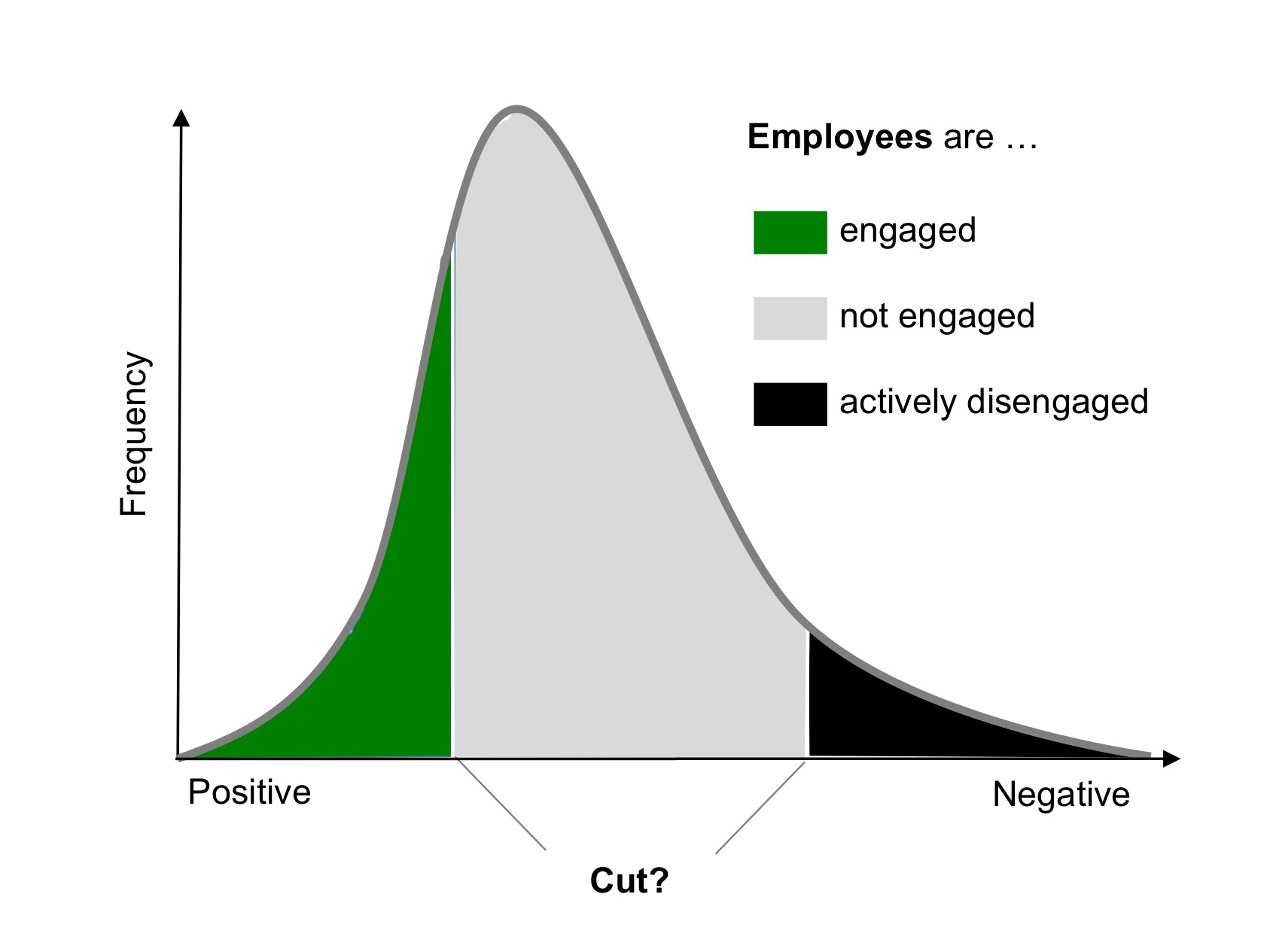

The reality in the workplace is often different. There, reaching a level of psychological safety would certainly be recognized as progress in many areas. Therefore, it is not surprising that especially in these, sometimes creepy, work realities, the desire for less social threat and mutual acceptance is widespread. In my practical work, I am often enough faced with such working environments. Do we have to assume that these spooky work realities represent a normality? I would disagree. Admittedly, it is not uncommon to point to the frightening results of the Gallup polling institute, which supposedly finds with steady regularity that four out of five employees are not engaged or actively disengaged. However, I have already described elsewhere what to make of this study.

At the same time, it is already more than 60 years since the great Douglas McGregor (4) coined his Theory Y and the idea of a self-determined, creative human beings and employees, seeking for meaning and purpose. Since digitization at the latest, we not only talk about agility, but also find it more and more frequently in knowledge-intensive working environments in particular. Then in 2014 we celebrated the great book by Frederic Laloux (5), who described the realignment of organizations like hardly anyone else. He too focused on the self-determination of intrinsically motivated people as well as the structures that are needed for this. In Germany, “New Work” is on everyone’s lips. No one knows exactly what this really is, but the idea of meaningful, self-efficacy and self-direction is certainly at the heart of this daring idea. And now we are articulating the claim that employees should fear less in their immediate work environment, in their teams? That honestly seems like a step backwards to me.

But fortunately, there are also other working worlds in which psychological safety seems not to be required, simply because people are already much further ahead. We are observing a generational change in the management levels that promotes other values and ideas than oppression and servitude. In a figurative sense, one could think that these working worlds and their leaders have grown out of the infantile phase of needed safety. Especially in knowledge-intensive working worlds, these working worlds should serve as a model for us. Psychological safety can be a way there, a kind of infantile early stage. But as the ultimate goal, it should never be enough to be truly innovative and competitive.

When operationalizing a concept, it is a good idea to put it into statements. These statements then reflect the respective claim. To give an absurd, extreme example, imagine that the claim to “good leadership” is represented by the following statement: “My direct supervisor only hits me when it is really justified”. In this case, of course, one would have to counter this claim by saying that a manager should not only not hit, but should also treat his or her employee with respect and appreciation – at least from today’s perspective.

Amy Edmondson has operationalized psychological safety using seven questions (1). They reflect the claim she postulates in knowledge-intensive domains. Now I dared to develop a counter-proposal (in italics) that I assume should reflect the entitlement in adult, knowledge-intensive work environments. Three of Edmondson’s questions are worded negatively (marked with an asterisk), so a rejection would argue for psychological safety. I have formulated my counter-proposals in positive terms throughout, i.e. reversed the meaning.

- If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you.*

In this team, errors are regularly discussed, and improvements are derived from them. - Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues.

The members of this team actively take up problems or difficult issues and try to solve them. - People on this team sometimes reject others for being different.*

People in this team value the individuality and individual characteristics of others. - It is safe to take a risk on this team.

In this team, risks are discussed, weighed up and one has the courage to take them if necessary. - It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help.*

The members in this team consider it their natural duty to support each other. - No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.

In this team, one actively, controversially and respectfully engages with the ideas and perspectives of others. - Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized.

In this team, I fulfil my responsibility to actively contribute my unique skills and talents.

As you can see, I have been guided by three thoughts in my counter-proposal. First, creativity, innovation, learning and development on the part of employees require a high degree of personal responsibility and courage. Secondly, it is about more than just avoiding social threat and mutual acceptance. Thirdly, the performance of a team is not only a question of leadership, but the result of the interaction of all team members. The latter aspect is not explicitly clear from Edmondson’s questions. In her book, however, she primarily addresses the role of leaders and provides illustrative examples of this.

If I were CEO, I would not accept Edmondson’s original questions in an employee survey and as a leader I actually don’t. They would simply be too weak in their claim for me.

(1) Edmondson, A.C. (2019). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

(2) Ainsworth, M.D.S. (1979). Infant-mother-attachment. American Psychologist, 34, 932-937.

(3) Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books.

(4) McGregor, D. (1960). The human Side of Enterprise. New York NY: McGraw-Hill Pro-fessional.

(5) Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations: A guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage in human consciousness. Brussels, Belgium: Nelson Parker.